Ars Pro Domo

Zeitgenössische Kunst aus Kölner Privatbesitz

(Contemporary Art from Cologne's Private Collections)

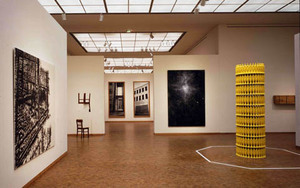

Museum Ludwig Köln, 22.5. - 9.8. 1992

Curator: W.D.

(Catalog)

Blindmen, Throw Away Your Canes

A Discussion with an Art Collector on ARS PRO DOMO and so-called Art after Art

Mr. Dickhoff, in ARS PRO DOMO you have put the artists' generation of the eighties on show, a generation to which you yourself belong. You have over the years accompanied these artists in exhibitions, catalogues, books, and other publications. You have very close contact with them and insight into their work. The unusual choice of title broaches many questions. Does it anticipate a definition of the exhibition?

The title is, first of all, meant to name the exhibition and not to identify its thematic content. It also is not intended to signify an overriding concept. The content of ARS PRO DOMO can be found in the form/content of the artworks themselves. But in considering the possibilities of interpreting ARS PRO DOMO , one should keep in mind the felicitous correlation between this exhibition and the unusual constellation characteristic of the art scene in Cologne. ARS PRO DOMO means "art for the house" one's own house and one's home and all one's homes with all their rooms - be they mental, intellectual, psychosomatic, museum rooms or everyday rooms - in which "you yourself" qua art search for a domicile. And, by way of a hint in another direction: there is one painting by Georg Herold entitled Ars Pro Deo (Kölner Dom), which directs your attention to the simultaneous desire for transcendence and a House and Garden-type life in art. However, I would prefer not to dwell any longer on this point but would rather leave it up to each individual to wander on his own in the semantic field mapped out by the constellation of the artworks.

Where is the thematic emphasis of ARS PRO DOMO to be found?

ARS PRO DOMO is a small and concentrated portrait of my art generation, selected from the contents of art collections in Cologne. ARS PRO DOMO is an attempt to show the specific qualities of this generation in a small condensed version. ARS PRO DOMO is therefore not an exhibition on art collecting in Cologne but rather an exhibition essay with excellent pieces from private collections. With it, the active influence of the collectors in forming the significance of the art scene in Cologne becomes part of it. But this, of course, also says something about the import of the art market as it influences exhibition making in general.

What do you mean by this?

Every museum exhibition today is to a great deal dependent on what is and what is not on loan. By limiting this exhibition to Cologne's private collections, I make this limitation part of the exhibition. The subtitle of ARS PRO DOMO is a sign for the presence of the art market in the way art can be presented today.

You emphasize the extraordinary character of the art scene in Cologne. You were born in Cologne and claim to be a child of this scene.

Yes, that is correct. But I must add that it is not clear to many non-Cologners, and even to many Cologners that Cologne has grown in the past few decades to become perhaps the most important art scene next to New York. For artists, critics, collectors, gallerists, museum curators, and art book publishers, as well as for all others engaged in some way in the field of art, Cologne has taken on the role of a platform from which crucial impulses emanate concerning what counts today as art, as well as what will count as art tomorrow.

How did this come about?

There are many reasons, which I can't go into now. It began, so it is said, with the trade in relics during the Middle Ages, which was centered in Cologne. Apparently, enough "true" relics changed hands for the pope to impose a ban on further importation. This means that in Cologne art of the highest quality has always gone rather freely hand in hand with its trade.

Is the art that is created, shown, traded, and discussed in Cologne also represented in the private collections of Cologne?

Yes, in a quantity and of a quality that continually surprise me when I visit the collections.

The focal point of the exhibition "Köln Sammelt" ("Cologne Collects"), which the Cologne gallerist Rudolf Zwirner organized in 1988, was on the high-quality established art of the fifties and sixties. In your exhibition the emphasis is placed on the younger generation of the eighties. How would you describe the age of your generation?

It, of course, isn't determinable purely by the year of birth; quite apart from the fact that "generation" is, primarily, a question of attitude, although attitudes are not necessarily dependent upon a generation. The large majority of artists who are shown in ARS PRO DOMO were born during the fifties, had their formative art experience in the sixties, and then went on to commit themselves in the course of the seventies to art. For more than fifteen years now their work has been hanging in many galleries and museums in Europe as well as in the United States, and they are at the very seat of discussion about contemporary art as it is documented in international art magazines. Their artistic development is closely tied to the Cologne art scene, and many of the most renowned artists of this generation are leading personalities within it.

For example: Rosemarie Trockel, Walter Dahn, Hubert Kiecol, Georg Dokoupil, Martin Kippenberger, Siegfried Anzinger, Andreas Schulze, and Georg Herold - all living in Cologne. But also international artists like Cindy Sherman, Philip Taaffe, Franz West, Mike Kelley, George Condo, Richard Prince, the pair of artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Robert Gober, Günther Förg, Jenny Holzer, and Albert Oehlen, all of whom, though not living in Cologne, have over the years been present here, not only through their works and their galleries but also personally.

With ARS PRO DOMO comes pars pro toto, that is, Cologne as a city of art whose international prominence has been formed by its close connection with New York. How do you account for this aspect?

Cologne also has collector initiatives with Paris and Madrid as well as with London and Italy. For my generation of artists, with which ARS PRO DOMO is primarily concerned, however, the transatlantic tie, with its priority for the German-speaking countries, is the dominant one. This can be seen in "ARS PRO DOMO ," but only insofar as it doesn't contradict my knowledge or convictions.

Are the activities of private collectors in Cologne tied closely to the most engaged gallerists in Cologne and to Art Cologne?

Yes, but to international galleries and fairs as well. I should add here that, for a long time now, collectors have been taking part not only passively but also actively and constructively in the discourse on art. The collectors' activities in Cologne are part of a lively interaction in which the artists, their supporters, and their opponents form a hub with supporting and adverse axes leading out of the city in all directions.

Exhibitions are often judged by their unifying concept. Could you say something about the concept underlying ARS PRO DOMO ?

I view overriding concepts for exhibitions rather critically because of the tendency for art works to be used in such cases as illustrations for preconceived ideas. I take the art pieces that I show seriously, and don't like to hide them behind ideas. ARS PRO DOMO is a welcome opportunity for me to compile an exhibition on the basis of the quality of the individual pieces of art, and this could also be an opportunity to discuss the exhibition from this perspective. In other words, the selection and constellation of the works displayed here are the conception of this exhibition.

What criteria did you use in selecting the artists for ARS PRO DOMO ?

Gottfried Benn once said: "The opposite of art is not nature, but good intention." And this criterion sifts out quite a few. This means that ARS PRO DOMO is an art-critical statement and not a balancing act between my convictions and the priorities of the Cologne collectors. I intend to exhibit in an exemplary way the most important attitudes and, with few exceptions, the most original artists of my generation in a small, condensed selection - no more and no less. The fact that this is possible turns ARS PRO DOMO into a compliment for the Cologne collections as well as for the entire Cologne art scene.

Could you name some exceptions?

The most significant Italian artist of my generation, Francesco Clemente, has not been collected - apart from a few beautiful small works on paper during the period when Paul Maenz showed him. Other exceptions are Julian Schnabel, Tim Rollins and K.O.S., Cady Noland, Haralampi Oroschakoff, and Michael Krebber.

What is your feeling for the reason these artists haven't been collected in Cologne?

Michael Krebber, who, by the way, lives in Cologne, has not yet been noticed and bought by the Cologne collectors. Perhaps the reason is that he allows his works to be sold as art only to the extent that they function as an extensive contemplation of that which, when, how, and why count as art.

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. form a collective built upon a teacher-pupil relationship. In this case, it is difficult for the collector to impute to their work the still popular myth of the creative individual. This problem was also one that confronted the Mülheimer Freiheit, since they painted pictures of multiple Egos during the early eighties, thereby contributing to the disintegration of the bourgeois art Ego. What one indeed finds almost exclusively in the collections, however, are pictures attributable to the "individuals" Hans-Peter Adamski, Peter Bömmels, Walter Dahn, Georg Dokoupil, Gerhard Naschberger, and Gerhard Kever. Julian Schnabel, David Salle, and Francesco Clemente have always been too expensive for the younger collectors. And in the older collector echelons one can sense an aversion to the successful younger artists, which has made the quality of their work virtually invisible to many.

Have you noticed differences between younger and older collectors?

The Cologne collectors have tended to collect the art of their own generation. Almost all of them also have works by older or younger artists, but the priority is clear. Older collectors often have many pieces by a few artists, younger collectors prefer fewer works by proportionately more artists. This is a tendency that has been influenced by price developments, but also by different attitudes. Almost without exception, collectors under forty do not consider themselves collectors. Not because they don't possess enough art but because they feel that the notion "collector" is inappropriate for their way of living with their art. This, however, is a broad topic that ARS PRO DOMO doesn't explicitly deal with.

Have you noticed any financial limitations on the acquisition of artwork with the Cologne collectors?

There aren't any. There are, however, limitations in consciousness, in perception, in devotion to art, in the need for compensation, in thinking. And there are those caused by fear and/or angst. However, there are also processes at work here that are normal. For example, a tendency to an aesthetic self-confirmation arises when you buy from young artists only what fits in with what you bought in your own generation. In other words, someone who is now fifty and collected Cy Twombly finds himself attracted by works in the new generation that look like Twombly, often only watered-down versions of the original and far removed from the specific contribution of the younger art generation.

You haven't included in your exhibition artists like Georg Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Anselm Kiefer, who were omnipresent in the eighties.

You have named some very good artists. I myself consider Georg Baselitz's latest paintings and sculptures to be especially very fine works. But in this connection you have forgotten A. R. Penck and Imi Knoebel, for example. First of all, these are not artists of my generation. Sigmar Polke, Georg Baselitz, and Gerhard Richter were even, in some cases, their teachers. Second, I believe that the time has slowly come to concentrate on the specifics of those artists who are approaching the threshold of their mature work, not as professed in theory but as can be seen in their works, as speaks from the form they use. And this remains - partly due to the unbearably indifferent matter-of-courseness of hypermodern art effects in the eighties - still largely unknown.

The artists of the eighties that you show are known for their large formats and their spacious installations. Can you do justice to them in the limited space at your disposal?

I can't do justice to them and don't choose to. In ARS PRO DOMO I don't show large spacious installations but focus on the individual paintings, sculptures, objects, and photographs. As curator, I like to stand back behind a constellation of artworks that themselves allow you to see what they have to say - through the manner in which they attract or repel, confirm, elucidate, or question one another.

The special aspect of your exhibition is certainly its intimate character. We have become accustomed of late to megaexhibitions. What is the advantage of a smaller, more intimate exhibition?

I have nothing against large exhibitions. The criticism against them, which the art scene appears to agree upon, seems too fashionable for my taste. The advantage of a smaller exhibition is that one can't revert to the pseudoaura of overstaging or mood-creating bluffs, so that the specific quality of the individual works takes on more importance. It's not easier. In fact, it's an advantage that is coupled with more risks, especially when dealing with relatively unknown artists. But this is precisely what interests me.

We are in the dokumenta year of 1992. We have Jan Hoet's list of artists on hand. In looking through it we noticed that only ten of your artists are also participating in Kassel.

The majority of the most interesting and characteristic artists of my generation cannot be seen in Kassel. But that is normal.

You speak of what is characteristic for your generation. What is characteristic of these artists?

First of all, it is what the works have to say by virtue of their form, and I am not prepared to replace this - and this is what art is all about - by any theoretical standpoint. But I can say something about the changed political conditions from which we started out at the end of the seventies and the beginning of the eighties. It was a situation in which we were caught in a network of appropriation procedures and confronted with the growing immanence of a symbolic order. You found yourself incorporated into the establishment at the very moment you were revolting against it. Appropriation was no longer something that one could avoid but something that at every step you took had already taken place. Even art no longer stood outside society as the Other, as that which undermined the identity of the establishment, as the incarnation of deviation from all norms and normalities.

On the contrary, much of what others (and even you yourself) had seen as rebellious subjectivity or as the authentic turned out to be an authenticity mock-up, and many well-intended efforts at critical or meta-artistic or political art revealed themselves to be a reproduction of that which they thought to have distanced themselves from or have overcome. And this applied as well to the intentions of a highly responsible Conceptual Art reduced to minimal signs of self-reflection that confronted young artists during the seventies as an academic status quo, as an institutionalized norm. The hopes for change that are linked with art turned out to be insincere and in many cases deceptive. A fog of postideological interchangeability and indifference had arisen in combination. And it was this situation that my generation had to face.

In this changed situation, the good old forms of provocation, opposition, resistance, protest, deviation from the norm, criticism, and subversion were no longer effective. New ways of artistic opposition had to be found. From the very beginning these new means of revolt had to have an in-built veto against itself, which was misunderstood as irony.

The precipitous development in the market often made the works of these artists appear fashionable, cynical, and affirmative. Aren't they just that?

In an atmosphere of indifference that tends to neutralize all the differences - which was in part brought on by a whirlwind development in the art market - art can no longer not be all this. But it is all the more important that art not just be this. For this reason, attitudes and strategies are necessary that don't just harmonize the contradictions under an avant-garde facade, but play them out. A behavior directed against the self that is not without humor and that systematically breaks down every longing for unity or identity, for example. Or formulations that carry their own negation but, at the same time, take the risk of an impossible artistic statement, which means the assertion of an answer where there is none. There is no outside to the system, including the "system" of simulation. Even the Other to the system turned out to be merely the reverse side. This even applies to the hope attached to madness and schizophrenia. Artistic resistance today probably depends on the level of humor adequate to the awareness of the impossibility of artistic resistance. As Gilles Deleuze once said, "There is no understanding. There are only different levels of humor." In the end art exists either in this difference or not at all.

There was a time when, politically speaking, art was leftist. Where does it stand today?

Since the end of the seventies, at the latest, we have no longer been able to pretend that there is a clear concept of goodness which is subscribed to simply by deciding to dedicate your life to art. Any artist who believes he is sitting on the bough of authenticity, or in the cerebral convolution of pure negation that disappears somewhere between the brain's hemispheres, or in the pub of solidarity with all the underprivileged of the world (luckily dying in some far-off place), or in the crypt of spiritual subjectivity has been beguiled into stupid insincerity, mental deception, sentimental political self-adulation, or a spiritual mock-up. It might be a consolation to convince yourself that you are on the side of the good. And many critics and curators (not so often collectors) allow themselves to be gratuitously misled by conventional reassurances: in the name of what Jacques Lacan called "the good, please don't touch." This is, however, neither honest nor even moderately intelligent. On the contrary, it reinforces illusions that only weaken the contribution of art to the situation.

But what is the contribution then, if art is to be uncritically consumed and accepted by society as was the case in the eighties?

The acceptance that was in the eighties handed to my generation by the boom in the art market wasn't, in fact, acceptance. The artists who mistook the ringing of the cash register for acceptance quickly became cheap caterers to a cynical situation that the serious artists of my generation deliberately opposed. So-called acceptance is part of the more general indifference to forms, styles, and interchangeable images that these artists had to cope with in their own persons before they could even begin to operate with forms and colors.

As different as the works are that the individual artists in the end developed, what they have in common is, first of all, the knowledge that each and every one of them, no matter how resolute and contemplated, has a deceptive side, and second, the aim of articulating this knowledge. The point is, and always has been, to produce beauty as resistance, which doesn't harmonize the antinomies of art and life but shows them in their implacability and parallelism. And this requires, first, that you perceive, reflect on, and endure the fundamental irresolution of the situation. An artwork that smells of discursive reassurance - in other words, clings to a system of references that provides an illusion of harmony and a coherent identity - is an insult.

What new attitudes would, then, in your opinion, be more appropriate to the complexity of the situation?

What is at stake are new forms of artistic integrity, sincerity, and presentness. On the way here, within the course of the past ten to fifteen years, many double strategies, intentionally paradoxical attitudes and other productive "false tracks," have been tested. The strategy of taking falseness, kitsch, embarrassment, mimicry, lies, and deceit in art to the second power is something that, above all, Georg Dokoupil and Martin Kippenberger have made unforgettable contributions to. The intensity-program of disdain for all worn-out styles and ideologies, the blatant overtaxed content of the picture, the semantic opening up of abstraction, and many intentional paradoxical strategies that one could superficially describe as nonaffirmative affirmation or non-negativist negation can be mentioned here. Art became a possibility for the very reason that one knew that art was no longer possible. Just because (post)modern art was at its end, its ways and means could be released for new forms and, above all, for new meanings.

Have political or moral pretensions played a role in this?

Because art was at its end, it became an at least possible continuation of that which was at one time termed political engagement. But before overhastily priding oneself on morality, one tried to exert a certain amount of intelligence in order to avoid naivety, imprudence, and cynicism with the intention of arriving at as true a formulation as possible. Artists like Walter Dahn, Albert Oehlen, Rosemarie Trockel, Philip Taaffe, and Axel Kasselböhmer, of course, follow moral or, if morally necessary, immoral impulses, but only to the extent that knowledge of the insincere imprudence of moral art is present in the artwork itself. And here opinions differ. For anyone can pride himself on being moralistic in content.

Why is an artist like Felix Droese, who represented Germany at the Banal in Venice, not represented in this exhibition? As far as I understand, he has been collected in Cologne.

Are you sure that you want to ask me this question in this context?

Yes, why not?

Do you remember Felix Droese's work I too killed Anne Frank?

Yes, I do.

Then I would like to answer your question in the following way. There is one drawing by Albert Oehlen that depicts two tubes of oil paint. The label of one reads I helped Felix Droese kill Anne Frank and the other I, too.

Doesn't this drawing express a cynical attitude?

Apropos of cynicism. If one understands it as a conscious reaction to a situation in which one cannot not reproduce that which one deems no good, then cynicism is a first step. It creates distance to the cynical reality of which one is not only a victim but also a producer on an everyday basis. But cynicism doesn't lead to any artistic result. A good drawing is necessarily more, namely, a rejection of defeat, dependency, and injustice. And this also applies to the drawing I described. It isn't cynical but a modest attempt in a cynical situation to contribute to its clarification, before materials that can't defend themselves are put into the service of notions they can't measure up to.

And when is that not the case, according to you?

For example, Walter Dahn, one of Joseph Beuys's youngest students, has always seen his own work within the framework of Beuys's concept of expanded art and viewed it with skepticism. But he has focused on his quality of an intense poetic concentration of images and after the death of Beuys has agreeably abstained from pseudomagical installations. Since the middle of the eighties he has been working on, among other things, small silkscreen paintings in which he reduces the image to a figurative skeleton and deconstructs the "authentic" line by means of its technical reproduction without giving up its existential aspect. Indeed, it is through this technical distance that it becomes believable. These pictorial operations on the boundaries of painting are some of the most beautiful that have been done these past years.

A painting by Albert Oehlen is depicted on the poster for the exhibition and a photograph by Cindy Sherman on the cover of the catalogue. Can one take these two motives as exemplary poles for your artists' generation?

The complementarity of both these works revolves around an attitude axis without defining it. But is it necessary to explain this? A woman and a man, America and Europe, photography and painting. And in both cases there is a distanced and reflective Ego portrayed in the picture. But not as a self that imagines a need for portrayal. With Cindy Sherman, it is - as always in her work - a deconstructed Ego used as a model for photographically staging a non-individual theme by means of her own body. It is a photograph that she took on the occasion of an AIDS auction in 1987 in New York.

In Albert Oehlen's painting Krankenzeichnen (Sick[ness] Drawing), the self appears in the form of a worn-out model of the painter's Ego. A person is depicted who on his sickbed is holding the abstract result of his illness in his hands. A false clichè of the insane genius that even then didn't fit Van Gogh and doesn't even come close to touching the extreme acumen of an Artaud. Albert Oehlen paints it as a self-portrait and thus makes the authentic abstract-expressionist painter ridiculous, using himself as an example. He articulates the death of the artist as an autonomous subject but without ratifying it. He records it in the form of painting that probes its boundaries anew.

Do you believe in painting?

Roland Barthes once wrote, "To create art means to consider the desire for the impossible reasonable." This is especially true of painting. It is a very questionable, indeed paradoxical, medium. For me, on the other hand - not least of all also for this very reason - it is of very special interest. It no longer represents realities, and the fetish of its presence has also shifted into neutral gear. When one creates a painting today, one knows that it is impossible to create a painting any longer and that when one feels, for this very reason, incited to paint one, this can't be reason enough, which on the other hand also changes nothing about the simple human faculty and about the continually experienced necessity "to paint" or "to play the piano."

Therefore, when one paints a picture in which one's awareness about the impossibility of painting is apparent, that, on the other hand, doesn't exhaust itself in showing itself as such, but rather appears as a staging of a semantic opening - to so-called life and its constitutive structures - one does so without indirectly mistaking this appearance for realism, indeed knowing that a painting cannot not be abstract but that it is still possible in the act of painting to go against the grain of its own voice. In this way painting not only has something to say to art and, therefore, functions as concept painting that has been worked out of painting itself, it also does not give in to magical-political illusions and doesn't lose sight of the theme, a theme that Picasso said is an undefined one which can originate only in painting itself. Then one perhaps comes close to the conditions leading to the possibility of painting today.

But what I am rather modestly leading to here will become, I believe, clearer in view of good paintings like FN Romantic and Der Baum by Albert Oehlen, Stilleben mit Krähen by Axel Kasselböhmer, and Ein zerbrochener Tag 1 by Siegfried Anzinger.

Is there not something like a basso continuo of a hidden theme in your selection that serves as a criterion?

A focus on content as the center of attraction regardless of aesthetic loss was what served in the beginning of the eighties as the initial spark for a liberation in art. Important impulses have resulted from the systematic overtaxation of content. As such, it was, however, in most cases more a matter of experience than of result. Content richness in art can be tolerated only if it is nonillustratively transformed into facial structure. If this is so, then it is a criterion. But then it is no longer a content, but art. And this is the criterion. Which touches on what I have called the nonsurrogate, for which Günther Förg and Philip Taaffe provide good examples.

What do you mean by nonsurrogate?

The artist today can expose himself, even going so far as to pull down his pants; it still remains a surrogate of expression. If he knows this, then he can include everything that goes under the name of subjectivity. And here it begins to get interesting. It is here that the idiotic comes into play, that is, the manner in which one turns oneself into that which one was turned into. Jean-Paul Sartre termed it individualized generality. But however he may begin, the artist, now more than ever, cannot get around the fact that everything he does is, in principle, stigmatized as inappropriate, because the object that he makes public in his name is, on the one hand, a "nothing-but-art product" that exists in the scenario of the market, yet at the same time already asserts, as such, an (im)possible beauty and lays claim to freedom. This is why most of the products of art are so embarrassing, because this - even with the best intentions - doesn't show.

Why is this impossible?

It is a possibility promised by its impossibility, and this goes back to Immanuel Kant, who attributed to human reason the ability to formulate questions it doesn't have the competence to answer. This is not a bad description of the mental situation in which (not only) Europe has found itself since the opening of the East, and also the transatlantic art world. I am convinced that an art that faces the instabilities of the present sincerely and copes with them through artistic form is working on the conditions for the possibility of new competencies that may someday be integrated into the answers to questions that mankind must answer. A good piece of art is a small presumption in this direction. This I assert with the fundamental inadequacy of an artistic statement. But art is rare.

Doesn't this also apply to the meaning of art at a time in which - due to the opening of the East, to AIDS, to insurmountable ecological problems - priorities have clearly shifted?

I choose not to add to the discussion, quite popular at present, about the time-fixated Geist of the West and the timeless spirit of the East. The art of the Eastern European and Asian countries will begin to speak out ever louder and I hope also ever more beautifully. But this will happen on its own. It doesn't need our art-colonizing efforts. This is an important subject, but not one that is relevant to ARS PRO DOMO .

As to the other problems that you have broached and that are not at all new: catastrophe as a permanent condition in which we find ourselves, indeed, of which we are a part, has caused many artists to play out the scope of art much more precisely and to avoid context-ignoring, mindless crossovers. Art is also always wall decoration - precisely ARS PRO DOMO - or landscaping, and this leads to a more realistic intercourse with the sphere of art against the background of a constitutive context and its possible change. This also is a contradiction that will be played out in a good work of art.

But this dialectic in art is also not new.

But this is not a dialectic. Nothing is being synthesized. Art today is simply paradoxical. The attitudes are interesting that deal with a situation (not only) in art that can no longer be subsumed under a uniformity of thought without erroneously prettying it up and that develop corresponding strategies and adequate forms of reaction. This demands, among other things, an open approach to the surrogate character of contemporary art, such as Rosemarie Trockel, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, Albert Oehlen, and many others display.

But isn't a picture a unity in the end, even if it is a contradictory one?

No. It is a deconstructive construction, an artistic resistance that encompasses its own deconstruction. This can be seen in the combination paintings done by George Condo. A good painting is simply beauty that doesn't beautify its own impossibility. This isn't at all complicated, as the works of Rosemarie Trockel prove.

Can you illustrate this with other examples?

Just look at the painting Hell (The People of the Art World in Monet's Pond of Water Lilies) by Marlene Dumas, Rosemarie Trockel's knitted work Matrazenlager or the photograph Untitled #179 by Cindy Sherman that we have already talked about.

ARS PRO DOMO hints as well at the contemplation of contexts that help determine the meaning of an artwork. A picture can mean something entirely different in a collector's living room from the meaning it has hanging in a museum. Does the exhibition make reference to this?

Indeed. In the title, in the installation of the exhibition, as well as in this discussion of ours. However, I don't use the artworks as didactic material for the explication of shifts in context or meaning. The fact that (self)contemplation of their so-called contextuality is inherent in them and the fact that they don't exhaust themselves in illustrating this have, indeed, been a criterion for their selection. In ARS PRO DOMO there are works that fulfill this criterion and refer explicitly to the constitution of meaning. For example, three photographs by Louise Lawler are shown: one on buying, one on possessing, and one on the reselling of art. In the first one, a nice detailed study of selling strategies (This Drawing Is for Sale) can be seen; in the second, the private living room installation of an American collector couple, and, in the third, two of Schwitter's collages marked with the appropriate red dots at an auction where also pieces of the collection shown in the second photo are up for sale. This is - considering the quality of these photographs - a commentary on the journey of collecting that also many of the works to be seen in ARS PRO DOMO have made and have yet to make.

What meaning does art have for the collector in Cologne? Don't social prestige and speculation also play a role here?

A residence full of art is naturally also a place where that self resides that is attempting to find its identity, having no home of its own. The buying of art for the purpose of acquiring psychosocial identity through the cultivation of art possessions always plays a role in collecting. But speculating on speculation is only very moderately present. I do not know of a single Cologne collector who in the eighties really went overboard and now goes into the auction houses shaking with fear. As for the meaning art has for the collector and gets from the collector, there are in the catalogue a number of photos that I took, along with the photographer Simon Vogel, at the collectors' homes. Here one sees how work vanishes in context, sets itself against the context for its own purpose, recovers its senses through private installation, takes on unexpected meaning, and so on. In these photographs you see a lot of art's life in the context of House and Garden.

Can making private collections public have any effect besides increasing the value of the collections?

Most of the works shown in ARS PRO DOMO have already been seen in a number of exhibitions, catalogues, and journals and have already attained their value in every respect. But besides this, I have nothing against increasing the value of good artworks. Reflecting on the difference between value and price - even in the strict economical sense - is a useful exercise. ARS PRO DOMO could be another chance to do so.

You talk of the specific quality of art and that it should become visible. How do you intend to set the scene for this? Even if you as curator step back behind the artworks, it still remains your stage production.

Even though every hanging may be a production, I would prefer to use the word "hanging." And for a hanging there are very concrete ideas and models. I am thinking of putting the work Modell Interconti by Martin Kippenberger - in which he used a monochrome gray painting of Gerhard Richter as the top of an end table - in a room together with paintings by Axel Kasselböhmer, a painter who sees his work as the continuation of a contemplated and intentionally distanced painting genre in the tradition of Gerhard Richter, who, on the other hand, also most likely feels closer to the humorous profanity of painting as a moral activity - as demonstrated by Kippenberger's works - than he does to the admiration of it. And if it works out, a piece by Reinhard Mucha will also be placed nearby. A pedestal that (as a sculpture) stands on a chair that also serves as a pedestal with a chair on it that again is a pedestal for the pedestal-sculpture and so on: the showing of showing as sculpture. This sculpture could enter into a not at all uninteresting dialogue with Modell Interconti and a painting that has been developed out of a responsibility to form. Whether and how this will work will, as always, be decided during the hanging. But this is the course that my thoughts on the constellation of the groups of pieces and individual works are taking.

Do you make reference in ARS PRO DOMO to the different phases that your generation went through during the course of the eighties? There was neo-expressionism, post-Conceptualism, and so on.

I am not showing my generation of artists retrospectively but qualitatively from the vantage point of its results. They could also have been seen at the beginning of the eighties. Most of them have, however, originated in the last few years, let's say between 1986 and 1991. Concerning their phases of development, I would like to say the following: viewed somewhat superficially, all styles of modern art were gone through in the form of neo and post "isms" in the eighties. It began with so-called neoexpressive painting, then ran through the comeback of the surreal, geometric, space-oriented sculpture, graffiti, installation art, and photography to the rediscovery of the conceptual endpoint. I say "superficial" because these so-called phases were displays of cyclic fashion accompanied by ecstasies of the market. The specific quality of the individual artists and their changed attitudes were concealed in most cases by misunderstandings connected with these nostalgic recycled forms of art history, according to their success or failure - here they both meet - to the point of invisibility.

Do you think that this goes for artists like Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente as well as for those who have remained unknown?

This cycle of fashion suggested a chronology of neostyle phases and staged a pseudocontinuity of post-kitsch, while precisely those artists who didn't function or who couldn't not function within this circulation were productive in openly interacting parallel processes. The neostyles of the season played a role only insofar as they couldn't be gotten around. One had to accept them as a fact, in order to then - for example, by means of grotesque exaggeration, or pretended ignorance - inactivate them and protect one's own work, which began where the styles, the isms, the art ideologies, the progress and innovation fetishes, and their art-substitute ended.

Although within the modes of cyclic fashion, artists were still defined according to past styles and media, for the artists themselves openness had long been a matter of course - not at all in the sense of multimedia playfulness. The scope of the media was, on the contrary, defined very carefully. But even artists who concentrate on painting reflect, within painting itself, the increased complexity and dubiousness of painting gestures in the context of audiovisual realities. This almost moral identification of media and materials - like "painting is reactionary" or "painting becomes progressive precisely by being considered reactionary" or "the more technique, the more inhuman" and "the more burned wood, the more critical of myths" - this exaggerated ideological over-identification is no longer interesting. It obscures one's view for what a painting, a photograph, or a sculpture might have to say.

Could you name one misunderstanding that has come about by being ascribed to such nostalgic fashions?

From the places they have been assigned within the fashion market of the eighties, the American Richard Prince (who is considered the protagonist of rephotography) and the German Walter Dahn (who is thought of as belonging to Wilde Malerei) should have nothing to say to one another. In reality, not only are they friends, but their work is also interrelated. Both work with photography and silkscreen technique as possible means of (re)presenting the sore points of cultural images. In the case of Richard Prince, these are often sexually over-determined images of American culture; in the case of Walter Dahn, colonization images of the third world or pictures from childhood superimposed upon socialization. And both view critically blind expression and pseudointellectual conception, reality-lacking figuration and formalistic ornate abstraction, as do, by the way, all the artists that ARS PRO DOMO shows. But this is only one example of the art of this postindifferent generation still to be discovered independently of the postmodern art logos.

What does that mean for the individual artwork? If I understand you correctly, you still presuppose an artwork to be free of its contextuality.

No, not at all. Art is the art of setting a gesture that makes a difference and/or a shift of context in the midst of the contextual complexity of which it is a part. And to the same degree to which it is simultaneously a belling stag, a recreation kick, state art, or an analogue of compensation for those who produce sensible questions needlessly, it is the paradoxical presumption of not being all this. There is no outside to indifference. There is only the art of being in difference.

Do the notions of presence, aura, difference, autonomy, beauty receive, in this way, new meaning?

"Yes, yes, yes, no, no, no," as Joseph Beuys and Johannes Stüttgen correctly stated in their famous dialogue of the same name. Presence yes, but one with dirty hands. That is to say, art searches for presence, where meanings dissolve by burdening themselves with social meaning, and then deconstructs it, thereby creating visual possibilities of meaning. Wherever art touches real wishes by virtue of its beauty, it is still possible that art is "a possible model of freedom," as John Berger says.

Do you believe in the aura of art?

As for aura, I wish to say - with Walter Benjamin - only so much: The moment exists in which a picture opens its gaze on us and conveys to the viewer the memory of a lost humanness. This auratic experience sends you home with the feeling of a genuine incongruity, that only art - in rare cases, it goes without saying - can impart. This is, of course, a platitude, but a continually reccurring one.

Is the art of your generation as serious and as deep as you have portrayed it?

In art there is only the depth of its facial structure. And it has more to do with the tragic-comic and serious humor that doesn't take the personal blatancy of the artist all too seriously. A personal example: Martin Kippenberger once was beaten up badly by youths when he was a business manager of the discotheque S.O. 36 in Berlin. He used a picture showing himself coming fresh from the doctor with a broken jaw and nose as the basis for a piece of work he entitled Dialog mit der Jugend (Dialogue with Youth). In other words, an artwork that shows presentness "is a healthiness, a superior style, a good mood - but at the height of an inner despair." This was written by Albert Camus in 1954 in his diary, in a year in which many artists whose works can be seen here were born. ARS PRO DOMO is an invitation to experience art as a good mood in this sense.

Mr. Dickhoff, I thank you for this discussion.